The role of government in providing for its citizens has been a controversial issue in US politics. Welfare and healthcare are by far the most important issues when it comes to government involvement. And yet, there is another issue that, while not as prominent in public discourse, is especially pertinent to me and many of my peers: the affordability of higher education.

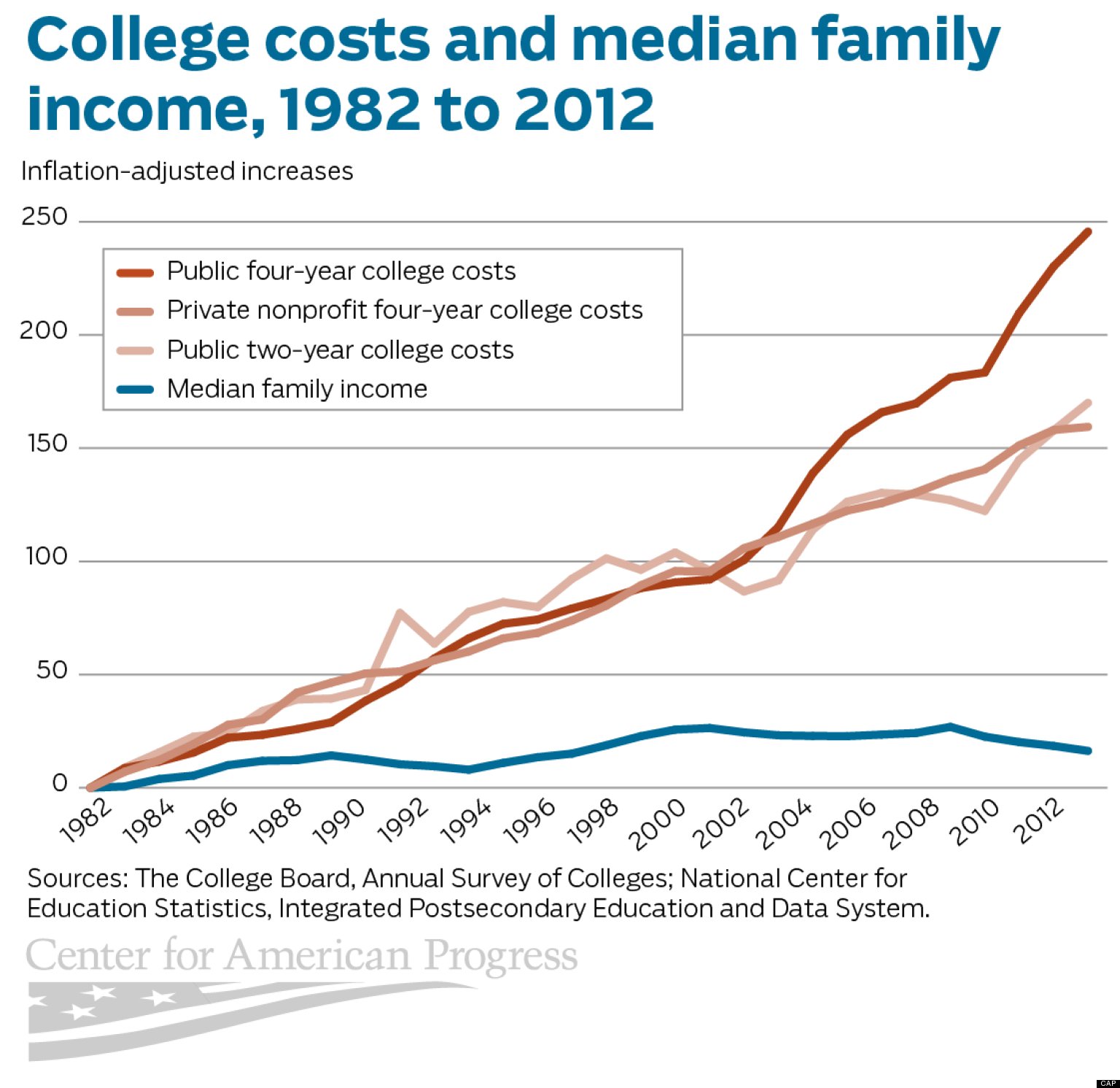

Public higher education, the traditional avenue to a college degree for those unable to afford a private college, is now out of reach for most people (unless, of course, they’re willing to go into debt). And the costs, as can be clearly seen, show no sign of dipping.

Now compare this to, say, Germany: tuition is free for all undergraduate students at all public universities. Remaining fees are minimal. The question that immediately comes to my mind is obvious: why don’t Americans do as the Germans?

Opponents of free higher education will argue that such a move is financially impossible. With a national debt of over $21 trillion, the last thing the federal government needs is to spend more; this will presumably weaken the economy further.

Or will it?

According to one study, people who go to university earn $17,500 more than those who finished their education in high school (and that number is only for those between the ages of 25 and 32). Higher education, simply put, means higher salaries and steadier employment. Education is the means by which the poor may elevate their condition. It is the great equalizer, to loosely quote educational reformer Horace Mann.

Education, as has been demonstrated, means more pay, and more pay means more spending. One person’s expenditure is another’s income, increasing his or her income in turn. Should this other person also get a college education, then his or her spending will increase for the same reason, thereby increasing the income of yet another person. This self-reinforcing progression is what improves the social and economic health of a country; a nation of college graduates is likely to be a nation of high standards of living and economic growth.

Of course, this cycle takes time to run its course — time that will see the national debt skyrocket if free education is to be made government policy. In light of this reality, I propose a compromise: free public education for those below a certain income, no federal financial assistance for those above a certain income, and lowered costs for those in between.

The reasoning behind this is straightforward. The truly poor are those most in need of social elevation; they are the ones who will benefit most from a college education, while also being the ones for whom it is most unattainable. The rich, on the other hand, can comfortably afford the most expensive colleges. Sixty thousand dollars a year won’t drive you into poverty when earnings are in the six digits. Last come the middle class, whose contribution must vary depending on income. They can afford higher education, though likely with varying degrees of financial burden — a burden that will be minimized proportionally to income so as to be fair.

Q.E.D.

Hey Daniel,

You do a very good job of addressing one of the greatest controversial issues: college tuition. You build a well constructed blog post that is very well supported with evidence that helps lead you to your proposed solution: people with different income pay different amounts of money for college tuition. Overall, I don’t think you need to add anything to this post.

Well written, hope to read more! -Jaehyeok

LikeLike

Daniel,

This post is concise and clear as always. I agree with your point, but I admit that this problem will take a long time to solve. Placing a question in the middle of the post is also effective in your argument.

It is difficult to criticize this piece, but I would suggest to perhaps create a more alluring introduction.

Well done!

Yaning

LikeLike